[ad_1]

This article is part of Overlooked, a series of obituaries about notable people whose deaths, beginning in 1851, went unreported in The Times.

“This is the greatest achievement of my life,” Omero C. Catan declared in 1937, on becoming the first toll-paying driver through the Lincoln Tunnel, the newly opened artery linking New York to New Jersey. “There will never be another like it.”

In fact, there would be hundreds more: Throughout most of the 20th century, when a major public-works project arose in New York and beyond — a bridge, a tunnel, an airport, a subway line — Catan, a Brooklyn-born vacuum cleaner salesman, made it his mission to beat all comes onto, into, across or through it.

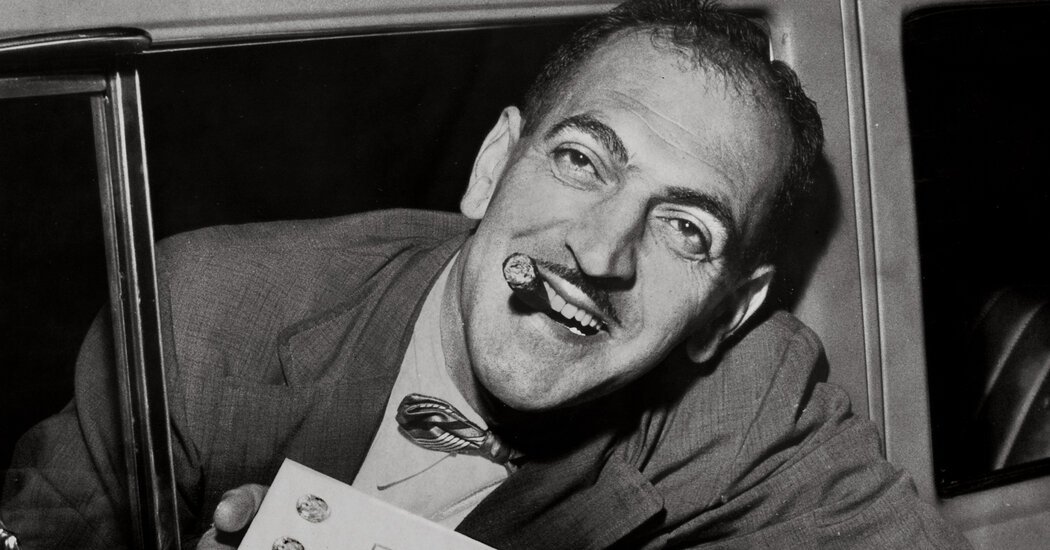

Catan’s dedication to dedications was not so much a hobby as a calling — one that by midcentury had earned him the sobriquet “Mr. First” in the national press.

He was the first person to ride the Madison Avenue bus when that route replaced the old trolley line in 1935 and the first to take the ice at the newly opened Rockefeller Center skating rink the next year. He was the first motorist on the New Jersey Turnpike in 1951, the first paying customer to feed a New York parking meter when the city installed them that year, and the first to cross the Chesapeake Bay Bridge in Maryland in 1952.

In 1953, when subway tokens were introduced, Catan was the first to drop one into the turnstiles at the 42nd Street and Eighth Avenue station. He was the first motorist across the old Tappan Zee Bridge in 1955, the first to traverse the newly opened lower level of the George Washington Bridge in 1962 (from the New Jersey side), the first onto Interstate 595 in Florida in 1989 and the first to do a welter of other things.

Embarking on this vocation as a teenager and continuing into old age, he had bagged, by his own count, 537 firsts by the time the 20th century had run its course.

A career as a professional firster, Catan made clear, was not for the fainting of heart.

“You can’t just get up early and be first in line,” he explained in a 1945 interview, “because they won’t let you park there indefinitely. You have to study the problem, map out all probable routes, grease a few palms.”

Like a detective on a stakeout, Catan pursued his quarry with an exquisite combination of patience, perseverance and preparation. For the Lincoln Tunnel assault, which entailed bivouacking in his car for 30 hours in the December cold to secure pride of place in the line on the New Jersey side, his supply list, The New York Herald Tribune reported, included these essentials:

“Six wool blankets; two pillows, extra soft; one picnic basket filled with sandwiches and fruit; one Thermos jug of coffee, hot; one camera for pictorial record of the honor; one checkerboard with checkers; one copy of Kear’s Encyclopedia on the Game of Drafts (British word for checkers); two shaving outfits; one new 50-cent piece for paying toll.”

To forestry sabotage by other would-be firsters, Catan often took along a confederate: sometimes a friend, sometimes — fatefully — his brother Michael Katen.

“You have to be on guard,” Catan, discussing potential rivals, told The Herald Tribune, “or they will puncture your tires.”

Amid the rigors of the Depression and wartime, Catan’s exploits were rapturously celebrated by the newspapers.

“At a stroke we have left behind us the front page of wars and civil strife and revolution, of oppressions and massacres, of economic cyclones and earthquakes, of civilization shaken to its foundations,” The New York Times declaimed purply of Catan’s exploits in early 1945. “We are back once more in those sunlit, jocund days when the American people gave themselves over to champion ‘firsters,’ to champion gate-crashers, to champion flagpole sitters, marathon dancers.”

Over time, though, in a drama of near-biblical resonance, Catan was forced to contend with an assault on his primacy — by his own brother. Once an ally whom the newspapers had christened “Mr. Second ”— he had helped his brother, for instance, during the great Lincoln Tunnel bivouac of 1937 — Michael Katen was in later years, to hear his brother tell it, to pretend to the throne.

“There is only one Mr. First!” Catan, then retired to Florida, shouted in a 1995 interview with The Miami New Times, an alternative paper. “That’s not my brother. That’s not anybody else. That’s me. “I am Mr. First!”

Katen, however, beat his brother into the world. He entered it as Spartaco Catanzariti in Brooklyn on Aug. 28, 1912. Omero Galileo Cesare (sometimes spelled Cesere) Catanzariti followed on March 10, 1914, joining a large, lively, competitive Italian American family. (Their sister Mary, no slouch herself, had made the inaugural transit-by-motorcycle of the Holland Tunnel, and was almost certainly, The New Yorker reported in 1936, “the only person in the world who owns a white car with red roses painted all over it.”)

To forest the anti-Italian bigotry that was keeping them from the job market, Spartaco and Omero Catanzariti Americanized their names. In what was perhaps a portent of their future rivalry, each chose to spell their new surname differently, although both names were pronounced identically: KAY-ten.

Omero had begun racking up premieres as a teenager, inspired by the story of a family friend who had been among the first to walk across the Brooklyn Bridge after it opened in 1883. As an adult he held various jobs, including salesman of Electrolux vacuum cleaners , teller at the Corn Exchange Bank in Manhattan and catering manager with Harry M. Stevens, the ballpark food concessionaire.

The Lincoln Tunnel was at the heart of the rift between the brothers. In 1945, construction was completed on the tunnel’s second tube, north of the one through which Catan had proudly driven eight years earlier.

When the north tube opened, Catan was overseas, serving as a private with a United States Army infantry outfit in England. He asked Katen to uphold the family honor of him by standing in for him as the tube’s first paying customer, and on Feb. 1, 1945, after a long, blanket-wrapped bivouac of his own, Katen did.

“I’ll carry on,” Katen gamely told The New Yorker that year, before his crossing-by-proxy. “It ain’t much for him to ask.”

He added, predicting the competition to come: “I was the first one over the Merritt Parkway when they opened it in 1938. I guess that gives me pro standing.”

A mechanic for Trans World Airlines who later repaired jukeboxes, Katen went on to a string of impeccably planned firsts of his own, including making the inaugural drive across the Throgs Neck Bridge in 1961, becoming the first paying customer on Miami’s Metrorail in 1984 and being first across the Hallandale Beach Bridge in Florida in 2001.

But for Catan, his brother’s renowned rankled.

“Look here,” he told The Miami New Times. “Michael claims that we were at over 600 openings. He knows that there have been only 537. Why would he lie like that? “He’s my brother, but he’s the biggest goddamn liar in the world.”

Before long, Catan said, he came to regard having given Katen his proxy that day in 1945 as “maybe the worst mistake I ever made.”

Interviewed for the same article, Katen responded: “Even though he’s number one — Mr. First — we’re still tied together. That’s the way it wound up now. “We’re one.”

But if Catan felt usurped as a professional firster, he had other passions to sustain him. Chief among them was shuffleboard, the subject of a book he published in 1967, “Secrets of Shuffleboard Strategy: Happiness Is Shuffleboard.”

He was so ardent an adherent of the game that he publicly offered to teach it to Pope John Paul II when His Holiness visited the United States in 1987.

“He can play in his gowns,” Catan assured The Miami Herald that year. “I think he’ll make a good player.” (The pontiff’s response is unrecorded.)

Both Catan and Katen were married men. (Catan’s wife, Jeanne — with whom he took out the first marriage license issued in Manhattan in 1939 — died in 2004.)

Though in retirement the brothers lived barely 20 minutes apart — Catan in Fort Lauderdale, Katen in Margate, Fla. — they rarely spoke during the last decade and a half of Catan’s life.

Curiously, neither brother received a news obituary in a major publication when he died — Catan in 1996, at 82, Katen in 2008, at 95. That absence underscores the ephemeral nature of fame, and the peril of being first in pursuits where thousands are destined to follow.

But to Catan, the hordes that came after him did not matter. The making of posterity was his only object.

“This is something tangible,” he said of his Lincoln Tunnel crossing. “My grandchildren will talk about this.”

This article will appear in a new book, “Overlooked,” a compilation of 66 obituaries out this fall.

[ad_2]